What Negative Thinking Does to your Brain

If you’ve ever found yourself trapped in a seemingly endless loop of negative thinking, or wondered why you fixate on a stray rude comment but easily forget compliments, you may have a culprit to blame: evolution.

According to Rick Hanson, Ph.D., a neuropsychologist, founder of the Wellspring Institute for Neuroscience and Contemplative Wisdom, and New York Times best-selling author, humans are evolutionarily wired with a negativity bias. Our minds naturally focus on the bad and discard the good. It was much more important for our ancestors to avoid threats than to collect rewards: An individual who successfully avoided a threat would wake up the next morning and have another opportunity to collect a reward, but an individual who didn’t avoid the threat would have no such opportunity.

Thus, the human brain evolved to focus on threats. Millennials are no stranger to stress and depression, especially when it’s work related—a recent study reported that around 20 percent of Millennials sought out help or advice in the workplace for depression—a higher percentage than any other generation. According to the Status of Women in the States report from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, Millennial women ages 18-34 report an average of 4.9 days of poor mental health per month, while Millennial men report an average of 3.6 poor mental health days. Our brains are highly attuned to stress, even when such stress is of the mundane variety and not at all life threatening.

“Negative stimuli produce more neural activity than do equally intense (e.g., loud, bright) positive ones, Hanson writes on his website. “They are also perceived more easily and quickly. For example, people in studies can identify angry faces faster than happy ones; even if they are shown these images so quickly (just a tenth of a second or so) that they cannot have any conscious recognition of them, the ancient fight-or-flight limbic system of the brain will still get activated by the angry faces.”

Hanson describes the brain as like “Velcro for negative experiences and Teflon for positive ones.” While some individuals may be inherently more optimistic than others, it’s generally true that in order for positive experiences to “stick” in our brains as well as negative ones do, these positive experiences need to be held in our consciousness for a longer period of time.

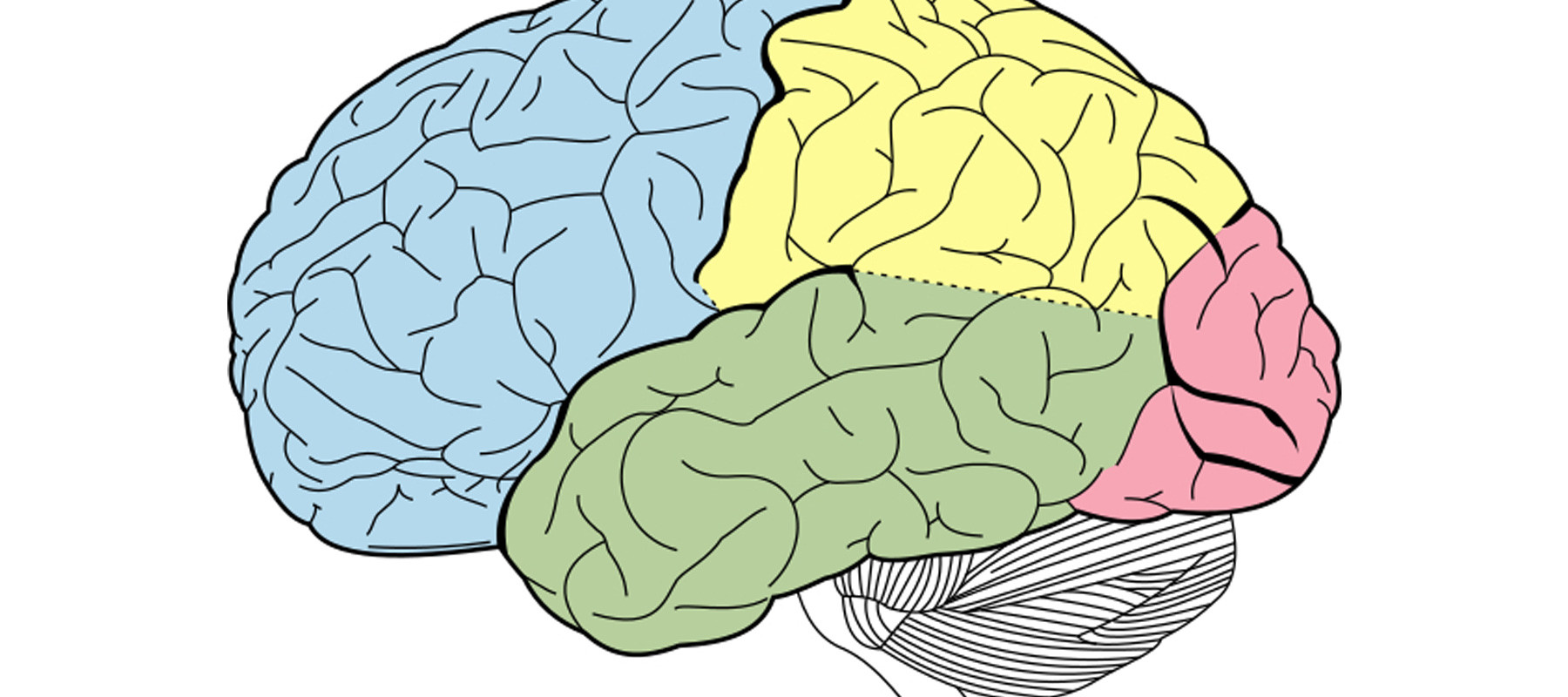

“The alarm bell of your brain — the amygdala (you’ve got two of these little almond-shaped regions, one on either side of your head) — uses about two-thirds of its neurons to look for bad news: it’s primed to go negative,” writes Hanson. “Once it sounds the alarm, negative events and experiences get quickly stored in memory — in contrast to positive events and experiences, which usually need to be held in awareness for a dozen or more seconds to transfer from short-term memory buffers to long-term storage.”

How Negative Thinking Changes the Brain

The more that an individual’s thought patterns trend negative and slip into rumination—continually turning over a situation in one’s mind and focusing on its negative aspects—the easier it becomes to return automatically to these thought patterns.

That’s not so great for our health. According to a blog post on Psychology Today, ruminating can damage the neural structures that regulate emotions, memory, and feelings. Even when our stress and worry is completely hypothetical and not based on any real or current situation, the amygdala and the thalamus (which helps communicate sensory and motor signals) aren’t able to differentiate this hypothetical stress from the kind that actually needs to be listened to.

Cortisol, a stress hormone, breaks down the hippocampus, the part of the brain that helps form new memories. Most people experience a peak of cortisol in the morning, but it can also spike throughout the day in response to stress. The more cortisol that’s released in response to negative experiences and thoughts, the more difficult it can become, over time, to form new positive memories.

In neuroscience, the expression “neurons that fire together, wire together” describes “experience-dependent neuroplasticity”—essentially, the concept that our brains are shaped by our thoughts and experiences. According to Hanson, the synapses in our brains that fire frequently become more sensitive. Our experiences and thoughts can lead to the growth of new synapses and even change our genes, altering the very structure of our brain. Or, as Hanson writes, “the brain takes its shape from what the mind rests upon.”

If you’re prone to negative thinking, this might seem disheartening. It’s easy to assume that we have no control over our thoughts. After all, they often pop up out of nowhere, and when rumination takes hold, it can be difficult to break its grip (I would know, I’m an accomplished ruminator). But the good news—and the basis of much of Hanson’s work—is that it is possible to change our thought patterns and even “hardwire happiness” into our brains (which is the title of Hanson’s 2013 book).

Shifting Negative Thought Patterns

Edward Selby, Ph.D., suggests in a post on Psychology Today that engaging an activity that fully occupies the mind, such a crossword puzzle, can be helpful in terms of breaking out of ruminative thought patterns.

Mindfulness—a non-judgmental awareness of moment-to-moment experience—and a regular meditation practice have been proven to be immensely valuable in shifting negative thought patterns and brain activity. One study published in Cognitive Therapy and Research in 2014 found that decentering, or stepping back to “observe thoughts and feelings as temporary and objective events in the mind,” can help mediate the effects of rumination in individuals with depression. Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn, founder of the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, teaches individuals to train their minds to cope with stress more skillfully (I discovered Rick Hanson through Karen Sothers, who teaches MBSR at the Scripps Institute for Integrative Medicine in San Diego, California).

Meditating regularly (there are apps for that: here’s a list) can not only help shift negative thought patterns—it helps the brain focus its attention and even slow the loss of brain cells. For individuals struggling with depression, meditation won’t necessarily substitute for therapy and/or medication, but it can work as a complement. Hanson also recommends practicing gratitude (keeping a gratitude journal and writing in it each morning is one way to do so), which can help increase psychological wellbeing.

To read the original blog post on attn: click here

By: Kathleen Toohill